Judique festival marks 250 years since founding

August 11, 2025

This year’s annual Judique on the Floor Days celebration, scheduled for August 3 to 10, will be a special one, as the community marks the 250th anniversary of its founding in 1775.

A detailed schedule of events will be well publicized once it’s finalized, but the festival promises to offer something for all ages – a village parade, historical talks, a community dinner, a movie night for the young ones, field events, pickleball and softball tournaments, and a variety of hands-on activities that illustrate the community’s story.

The founding of Judique began in 1775 when Michael Mor MacDonald from South Uist navigated the shoals and landed on the shore of what is now the site of a small day-park and marked by a cairn. He was searching for a suitable location for settlement by a group of Scots who were then living in St. John’s Isle (Prince Edward Island), but who wanted to find a place where they could own the land they farmed. Michael was married to Anne MacEachern from South Uist.

The MacEacherns were a large and relatively prosperous family, and the father was Hugh MacEachern. The youngest son, Angus Bernard (Aneas), was already in training for the priesthood. In those days the penal laws in Britain made Catholic worship illegal, and prevented Catholics from voting, holding public office, owning land, or teaching. There were penalties for Catholic priests practicing their ministry, so the Church functioned underground, and training was done in secret.

Their landlord, Colin MacDonald of Boisdale, had previously left the crofters of South Uist alone to practice their religion quietly and unobtrusively, but after his marriage in 1770 he began to enforce the ban and tried to make them convert to the Church of Scotland. He stood on the path with a big stick, hitting them to prevent them from going to their chapel, and then refused to renew their leases for their crofts if they did not swear an oath to convert. They refused the oath.

Meanwhile, Colin’s cousin, Captain John MacDonald, Lord of Glenaladale, had mortgaged his land in Glenaladale to buy a landholding in St. John’s Isle. He needed tenant farmers and proposed that those who refused to convert could move there. They would be settled near the Acadians who were already there. The MacEacherns were a large and influential family, and when old Hugh MacEachern and most of his children decided to make the move many others decided to accompany them. Young Angus Bernard was to remain behind to continue his training.

So, there was a large contingent interested in going, but most did not have money to pay for their passage. Glenaladale began buying provisions for the group but could not afford the cost of a year’s supplies as well as the passage money. Fortunately, the story was heard in a well-off parish in London, and that congregation raised money to help pay the passage of those who could not pay their own.

The ship Alexander was engaged by Glenaladale and left South Uist in May 1772 for the trip to North America and then continued around the small isles of Rum and Eigg, and along the shores of the Moidart area, picking up others who wanted to emigrate.

Landing on St. John’s Isle in late June 1772, the passengers of the Alexander were assigned tenancies nearby. There they found fertile land and a close community, but they were still tenant farmers. Glenaladale attempted to assist the

group but there were problems with supplies not arriving, and dissatisfaction with the tenancy system, and then crops failed. Some of those who had been forced out of their homes once were wary of remaining tenant farmers and still being subject to the wishes of a landlord, even if he were a benevolent one. Hearing that there was land available across the Northumberland Strait in Cape Breton, Michael MacDonald, an experienced sailor and sea captain with his own boat, headed across to scout out the site for his group. At that time, the points to the south and to the north extended much further out and curved toward each other, to form a very fine natural harbour opening into flat land, and this is where Michael landed.

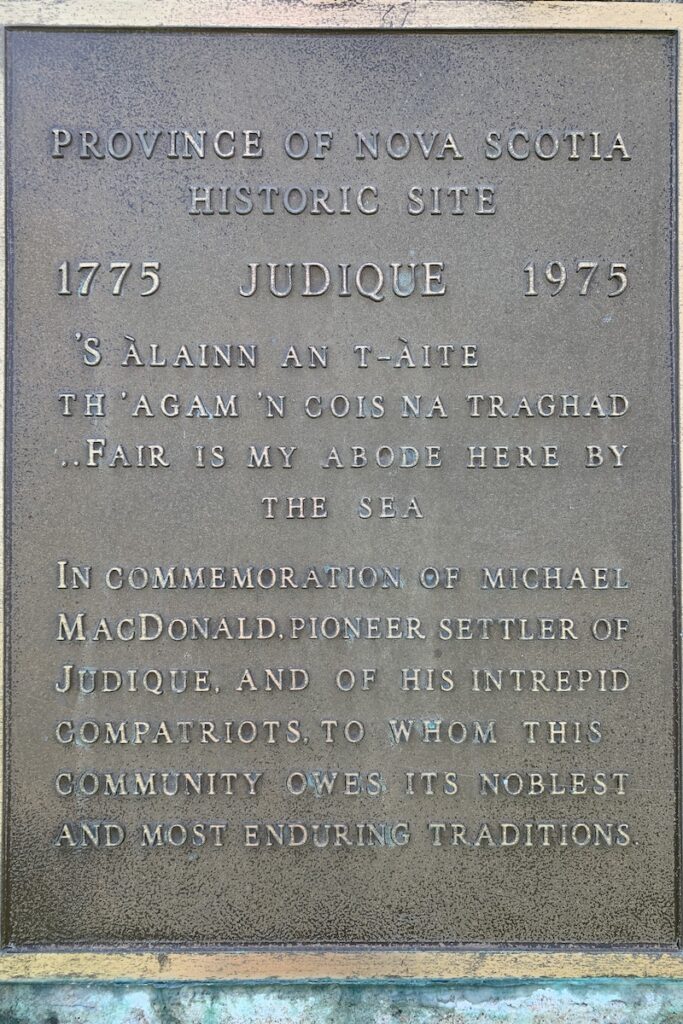

The ice closed in, and he was forced to remain while waiting for the waters to open up. With the help of the Mi’kmaq, he was able to spend the winter, and then headed back to Prince Edward Island. Shortly after, the group arrived to start a new community. They were soon joined by others and Judique was established. Michael MacDonald, who was a man of many talents, made the first Gaelic song in North America, O S’ Alainn an T-Aite (Oh Fair is the Place).

Of the children of Hugh MacEachern who had come to St. John’s Isle, four were included in that first group who came to Judique. Anne MacEachern was married to Michael MacDonald, Mary MacEachern was married to Robert

MacInnes, mason, Catherine MacEachern was married to Allan Ban Mac Donnell, and Ewan MacEachern was married to Mary MacDonald.

They were joined by Alexander MacDonald (Rhetland), John Graham (veteran of the American War of Independence) and Donald Ban MacDonald (Chloinn Sheamis), as well as John MacEachen (lain MacEachuinn), Blacksmith, Roderick (Mor) O’Henley, and Neil MacMillan, Donald Gillis and Hugh Gillis. Of course, most of these were married and had children, but the names of their wives were often not recorded on land grants or legal documents, except in church records, if these survive. Because Catholics weren’t allowed to own land, they were considered squatters. It wasn’t until 1789 that they were able to petition for grants of the land they occupied.

According to The History of Inverness County, the clan names in early Judique were Beatons, Chisholms, Campbells, Camerons, Grahams, Grants, Gillises, O’Handleys, MacDonalds, MacDonnells, MacDougalls, MacEachens, MacInneses, Maclsaacs, MacLellans and MacMasters.

However, Rev. MacEachern had arrived in St. John’s Isle in 1790, and the next year travelled to Pictou, where the first large groups of Gaels had landed, to encourage the Catholic ones to join their co-religionists in St John’s Isle or in Judique. This, along with harsh conditions in Scotland, and letters of persuasion sent back home, meant that settlers continued to arrive.

In 1804 a petition was made for the title of the property that was being used as a graveyard and the site of a small chapel, St. David’s. This was really the parish church, but as the penal laws prohibited Catholic churches, it was called a chapel and had to be owned (nominally) by an individual. But there was still no resident clergyman on the western side of Cape Breton, although there were occasional visits from Rev. Alexander MacDonald from Arisaig, from Rev. Augustin-Magloire Blanchet to Cheticamp, and from Rev. Angus Bernard MacEachern, who sometimes came from Prince Edward Island to administer the sacraments and to see his sisters. In 1808, Rev. Alexander MacDonald petitioned for 200 acres in Judique for the use of a Catholic priest and Father Alexander MacDonnell (a cousin of Thomas Ban MacDonnell, one of the first settlers), came to Judique in 1816. He was expected to minister to all of Inverness County except Cheticamp, and travelled to mission churches that were being built in Broad Cove, Mabou, River Inhabitants, and later Port Hood. He remained until his death in 1841.

With the growth of population, the small chapel in Judique was too small, so in 1820 a larger wooden one was built, which was later struck by lightning and burned. A site further from the shore was chosen for the larger replacement church and it was completed in 1860, with a new graveyard established beside it. In August of 1919 a strong southerly gale brought lightning that struck the wooden church (the towering height of spires and bell towers made a target for that hazard). Neighbours saw the flames and rushed to rescue statues and altarpieces, but the wooden building could not be saved. There were no telephones, of course, so the couple (and their families) who arrived the next morning for their scheduled wedding found only a blackened ruin.

The current stone church was begun in 1924 and consecrated in 1927. It is built from brown sandstone hauled from the shore by horse and wagon. Stonemasons were hired for the skilled labour, but the rest was provided by the parishioners.

Meanwhile, the settlers who had arrived in 1776 were busy clearing land and building shelters for themselves. They supported themselves with fishing and farming, as many had done back home, though they had to adapt to new conditions and a very different climate.

In early years the grain they grew was ground in the household with a quern, made with two small flat carved stones, but later several grist mills were built, powered by water running down from the mountain.

Fishing was an early occupation and that led into shipbuilding, sailing, and trading. Farming techniques improved and farmers had access to agricultural learning. A brick-making factory was built on the River Denys Road. Later, during the Depression, they built lobster-canning factories to sell their lobster further afield.

The settlers also focused on education and at one point there were more students from Judique attending colleges than from the rest of the island combined. And of course, there was the music and storytelling, a rich cultural tradition that the settlers had brought with them and that was nurtured in the new land. Three things sustained them in hard times: this cultural tradition; their deep religious faith; and a strong sense of community.

The celebration being planned for this summer is based on those three things and marks the 250th anniversary of the landing of Michael MacDonald on this shore.